Godot is a 2D and 3D game engine that has been on my radar for quite some time. Reviews for it are mostly positive, the scripting language is similar to Python (yay), and it’s open source.

The open source bit is pretty cool not just for philosophical reasons. It reduces your cost of development. For those living in countries with currencies weaker than USD, what may be a low monthly subscription or generous revenue cap still makes a sizeable dent in disposable income.

This post is just a write up on what I liked about Godot, what I didn’t like about Godot; all the interesting experiences that came up while creating my first game.

To start this journey, I first determined a structured way to learn the engine.

Learning Path

I’m a web developer, hence why most of my previous ventures into game development have come through Phaser. I did tutorials for Unity and Unreal before, but those were a couple of years back so using Godot felt as close to a brand new experience as it could have been.

As with most new Godot users, my starting point was their getting started guide. I read everything from the introduction to my first Godot game tutorial. It’s necessary reading to get an understanding of the engine’s design and key features. Admittedly, it took me a while to truly understand all the information.

I enjoyed the tutorial game that was created, it’s casual enough to be fun. The export section also shows you how to make it Android friendly - you create an app on your first try!

However, after finishing that game I did not feel confident enough to go on a project of my own. Even after looking at the example games created by the Godot team, I felt as if I needed a guiding hand.

Blogs and YouTube Videos

I scoured the internet for tutorials. The community seemed popular enough that I was pretty sure there would be a haven for Godot related resources. A lot of resources are available for version 2.1 and 3.0 - I used 3.1, the latest stable version at the time of writing, so they weren’t immediately useful.

I looked at a few YouTube videos and read a few blogs. For the level and confidence I had, the best resource seemed to be Fornclake’s Asteroids tutorial. Small in scope and very well written - it was perfect. Well, almost perfect. It’s incomplete… the bits where you destroy the asteroids were never written. To its credit, I felt it gave me the tools to work on that myself. I opted not to as it would probably take me more time than it should to get it done.

I had a positive experience with Udemy when learning React, Phaser, and Unity. I saw some Godot courses when I bought a recent TypeScript course, it was time to have a second look.

Udemy Course - Discovering Godot: Make Video Games in Python-like GDScript

This course is done by two people who are super popular on Udemy and other platforms - Ben Tristem and Yann Burrett. They both made careers out of teaching people how to create games with different engines, they do a good job at it too. After looking at the alternatives I figured this course was the best bit.

Having read the Godot tutorial and other blogs, and coupled with my familiarity with Python, it may be too basic at times. I found myself skipping over things like what are if-statements. It’s not a problem that’s it there, it was meant for beginners after all. But you have a similar Python background you may find yourself skipping over those bits too.

However, don’t make a habit of skipping over things. The details about Godot were invaluable. As much as I read about the framework, this course does a great job of at least reinforcing how the engine works.

The first tutorial was to build a game called Loony Lips. It’s a simple game that generates a random sentence given 4 user inputs. It was super simple, the small scope was perfect. After that tutorial, Godot finally clicked for me.

The next tutorial for the course was a platformer. I always like to create something after completing a section in an online course, it’s a nice way to validate what I learned. So before moving onto the next class, I decided to make AV: Execute.

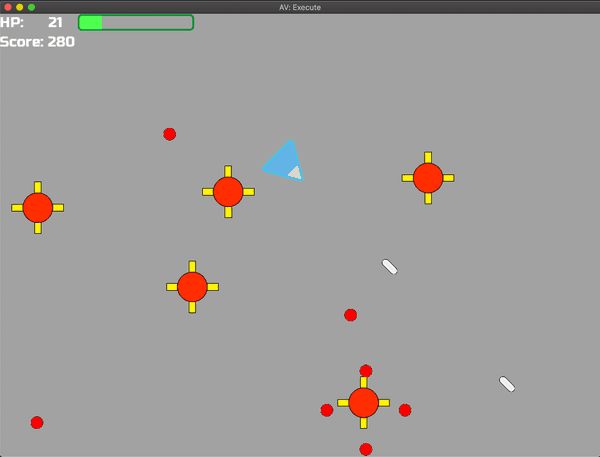

November Game Project 2019 - AV: Execute

I began playing Megaman Battle Network again… it holds up so well after all these years ♥! So the game I created would have its 8-directional movement. Heck, let’s just make it a game about viruses. In the end, I came up with AV: Execute.

It’s your standard fare swarm shooter - you’re in an arena and your goal is to derezz as many viruses that come your way. The last high score I recall getting was 400, not bad. All the code is available on GitHub and the super basic artwork was done by yours truly.

Making this game was fun. Godot is a good example of high quality open source software. From the start of the project, there were a lot of things I liked about this experience. Let’s have a look!

Things I Loved

The Software Itself

My experience with Unity was so annoying at times. Crashes were not so frequent that I couldn’t learn how to make games with Unity. It did happen enough times for me to notice it, and to be annoyed with it. Godot doesn’t give me any problems while running. I’m sure Unity in 2019 is probably much more stable now than a couple of years back, will let you know when I get into it again :-).

Godot is extremely lightweight, compared to Unity and Unreal at least. The application takes up about 68 MB of space! Unity after installing took up close to 1GB. Unreal I believe came up to roughly 8GB. For comparative features, this is simply marvellous. It’s also not a RAM hog like the others. So yes, you can use Godot with your 1 million Chrome tabs and it will be fine.

Scenes and Nodes

Nodes are like the atomic properties of an object. A scene is a group of nodes organised in a tree. Scenes can also instance other scenes. Godot games are made up of scenes, which in turn are made of other scenes and nodes.

This might be better illustrated. In Phaser, I would create a Player class that extends from a Sprite. I’ll add all the extra properties I need, like a score for example.

In this game, I created a new Player scene by first having an Area2D node. This node can detect collisions with ease. To make my root node, and therefore my Player scene functional, I attached the following nodes one level below:

- Sprite - primarily contains the image used for the Player

- CollisionShape2D - the collision boundaries for the Player

- CannonPosition - predefined position where the projectiles come from

- ShootTimer - predefined wait period between firing a projectile

- Identifier - a basic node I created to help manage collisions

- Blink (AnimationPlayer) - the animation that’s seen when a player is hit

That Player scene, as you can imagine, was instanced in my main game scene along with the Heads Up Display and others.

This system is super intuitive, and well explained in the main tutorial. I think most Godot users with a programming background would easily take to it. I would say the Udemy course gave more details on what each node was doing, and how to search the docs for the appropriate node.

Save a Scene Separately After Creation

Let’s say you’ve created a scene for a particular component, and parts of your scene needs to be reused. Godot makes it super simple to take a collection of one or more nodes and save it as a separate scene.

Godot will automatically instance the newly branched scene so everything would continue working as expected.

This is cool because it allows us to keep our project structured and modular at different stages of development. It’s not a groundbreaking feature, but it’s nice to have.

GD Script

If you know Python, you’re fine to get going with GD Script. Worried about performance? Don’t be, it’s pretty quick. The Godot developers first tried to use Lua, then Python. From those suboptimal experiences, they then made GD Script to take full advantage of Godot’s design.

What I love about the scripts is that they are embedded into nodes. This makes the nodes/scene system so much more powerful as scripts are used to extend a node’s functionality. Add to that the seamless integration between the editor’s UI and the scripts, what you get is a fairly flexible way to create a game.

Some things I prefer to code with GD Script. Other things I prefer to set in the UI. It doesn’t matter, it’s all fine. Having options is a good thing.

The Mono bindings are in development and the game developer community is pretty excited about coding with C#. That’s likely due to Unity’s popularity. I’ll most likely stick with GD Script.

Intuitive Menu Design

The GUI controls are super intuitive. Hierarchies are usually obvious with some basic UI planning. Mapping my design to the scene system felt straightforward.

Controller Support!

This is fairly standard in other game engines. As I mentioned earlier, my background is in Phaser, so I am accustomed to writing extra logic to get controllers to work. I was very pleasantly surprised to plug in my PS4 controller and play this game as expected, without any code or configuration. The controller settings have sensible defaults for the major brands - good job Godot team!

Version Control: Everything Is Text

I use Git all the time. Godot developers were playing chess instead of checkers here, all scenes are saved as text files. Therefore, version control systems play nicely with Godot from your first commit to your last. For reference, with Unity and Unreal there are extra steps to make it play well (pesky binary files):

- https://thoughtbot.com/blog/how-to-git-with-unity

- https://wiki.unrealengine.com/Git_source_control_(Tutorial)

Exports to All Major Platforms

Electron and Cordova do a job of export HTML5 games to desktop and mobile apps respectively. Even so, they can’t beat this experience. Exporting to all desktop applications was painless. So was creating an Android APK for the tutorial game. I haven’t created an iOS app as yet, but I don’t imagine that it’ll be painful.

Those were the key benefits for me. Let’s have a look at some of the pain points, thankfully there are not as extensive!

Things I Did Not Love As Much

Unfortunately, not everything was sunshine and rainbows. The positives certainly outweighed the negatives, but you might want to keep this in mind when considering Godot. As per usual, your mileage may vary.

macOS Catalina - Bloody Hell

My experience with Godot before upgrading to Catalina and after upgrading were remarkably different. I did the tutorials in Mojave and experienced little to no problems. These are some issues that Mac users may encounter when using Godot 3.1 on Catalina.

Version Control GUIs

I usually favour making small commit messages with descriptions of what changed and why. This helps to provide context when looking at why your code behaves a certain way and makes reverting less daunting. That doesn’t change with Godot.

However, as I make various configuration changes alongside code changes, using the command line to make granular commits became tedious at times. I’m very comfortable with the command line, I figured I would be more efficient with a GUI.

I downloaded SourceTree and GitHub Desktop, hoping to do a quick evaluation of the two so I can get to the main task at hand. Unfortunately, I could not run either of them.

I got the “can’t be opened because Apple cannot check it for malicious software”. My settings allow me to run software from anywhere, and I did not see the usual “Open Anyway” button in the security settings. They should sign their apps when making releases so this would never be a problem.

In the end, I used my default code editor, VSCodium - VS Code without Microsoft’s telemetry. It worked for the project and the time. I believe new releases of SourceTree and GitHub Desktop are signed, so I’ll give them a sometime soon.

Freezes When Moving Between Screens

I work with an extra monitor, on a great day two extra monitors. Life is better with more monitors! Godot looks great on each screen when it loads. Usually, I have my code on one screen, and I have the game running on the other. This allows me to see the debug messages I play with a scene.

Life after Catalina brought inconsistency to that flow. There are times I drag the running game to the second screen and it suddenly appears all blacked out. Restarting the player seems to fix it, but I rather not perform this ritual when debugging my game.

No Windows Taskbar Icons - Wine Doesn’t Work

Windows taskbar icon needs images in the special .ico format. That’s fine, imagemagick makes it easy to create those files from a PNG. However, for that .ico to be used when exporting, you will need to point Godot to your installation of rcedit - a tool that can change resources in an .exe file. Godot has a helpful guide on this process.

On Mac and Linux, to install and use rcedit we need to have wine installed. Wine may be fully working in Catalina hopefully by January 2020, you can read this thread for more information.

Till then, to get Windows taskbar icons on Mac you’ll need a Linux desktop VM or access to a Windows machine.

Exported PCK Files

Admittedly this is not the end of the world. Linux and Window exports in Godot come with a .pck file, which contains the resources for the game. It’s also meant to facilitate updates to a released game, for example, DLC.

For a small project like this, I felt it should be fine for Godot to embed the PCK in the executable binary. I imagine a user would prefer seeing one .exe file instead of two files to run a game. This feature used to be available in Godot 2.0.

It was intentionally removed in version 3.0 onwards for simplicity reasons. However, one GitHub issue led to a pull request, and it seems that version 3.2 will re-enable this feature.

For now, I export my Windows and Linux builds as a zip file that contains the executable and the PCK.

Conclusion

I enjoyed building this game with Godot. I was able to get into the paradigm of how things work quickly. I felt as if the engine gives me a lot of ways to make a polished game that can be shared on many platforms.

It’s also a nice sign that the pain points are specific to Mac, and will be resolved soon if not resolved already.

Going forward, I would like to finish my course to learn more fundamental Godot concepts. I also want to make games specifically for the iOS and Android, and have them on their stores.

Happy game developing!